A new study published in Current Anthropology may have solved one of the largest mysteries of ancient Mesoamerica—the language spoken in Teotihuacan, the vast metropolis that dominated central Mexico nearly two thousand years ago.

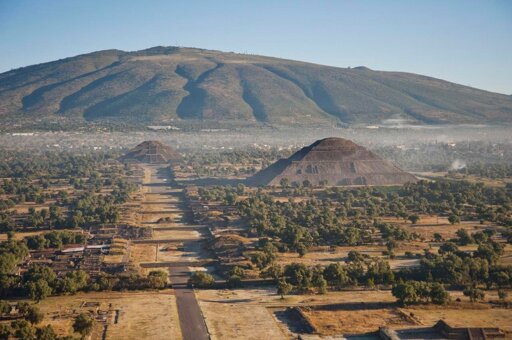

Teotihuacan, founded around 100 BCE and abandoned by 600 CE, was one of the largest cities of the ancient world, home to more than 100,000 people at its zenith. It was a cultural and political hub whose influence spread across Mesoamerica, with monumental pyramids, wide avenues, and intricate painted murals. Yet despite decades of excavation, a question has remained for years: what language its inhabitants spoke → what language did its inhabitants speak?

Researchers Christophe Helmke and Magnus Pharao Hansen of the University of Copenhagen now propose that Teotihuacan’s murals and artifacts preserve an early Uto-Aztecan language, the ancestor of later languages such as Cora, Huichol, and Nahuatl—the language of the Aztecs. Their study provides evidence for a direct link between the people of Teotihuacan and later Nahuatl-speaking populations, implying the Aztecs may be descendants of this earlier urban civilization.

The researchers’ conclusions derive from years of detailed examination of signs found on Teotihuacan’s murals and pottery. Scholars have wondered for a long time whether the images were merely decorative or represented a writing system. Helmke and Hansen think they do both: some signs are logograms, pictorial representations of entire words—a coyote for the word “coyote,” for instance—while others form phonetic compounds, or rebuses, that represent sounds, not meanings. This dual use of signs marks the system as a true writing system.