- cross-posted to:

- math@lemmy.world

- cross-posted to:

- math@lemmy.world

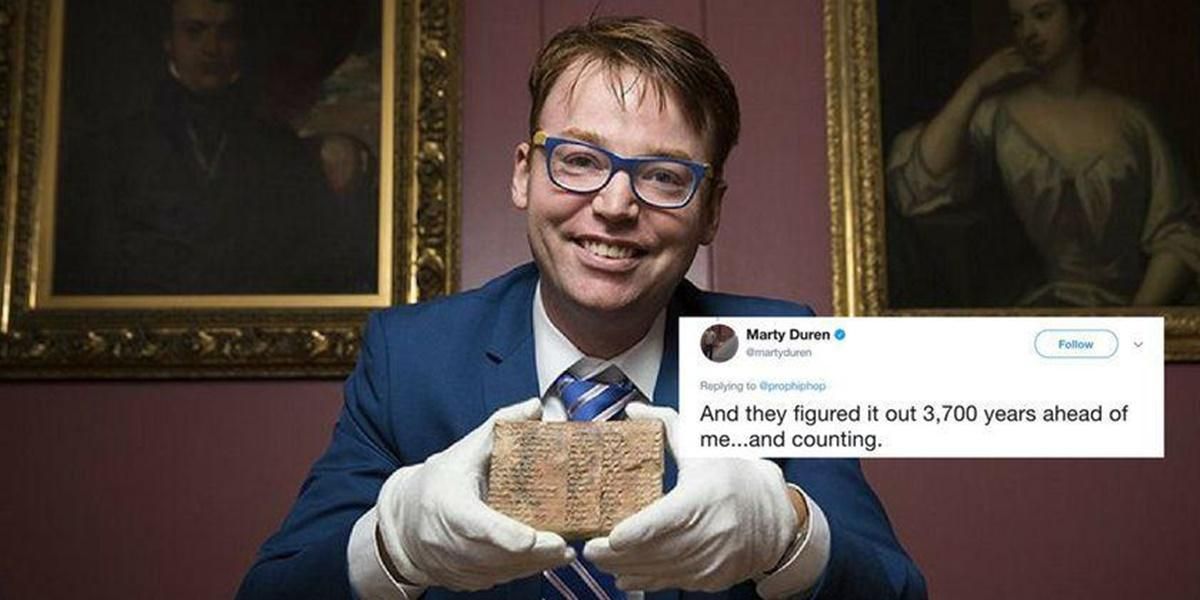

They give a bit more context in this video. (from 2017)

By the way, I got that link from an article in The Guardian, and I can’t find anything in either of those two articles that really adds on top of what was known in 2017. It could just be hard for a layperson to understand, and so was oversimplified?

TLDW is that researchers have known for decades that this tablet showed the Babylonians knew the Pythagorean Theorem for 1000 years before Pythagoras was born. So, that part isn’t new.

They seem to be saying that what’s new is that they understand each line of this tablet describes a different right triangle, and that due to the Babylonians counting in base 60, they can describe many more right triangles for a unit length than we can in base 10.

They feel like this can have many uses in things like surveying, computing, and in understanding trigonometry.

My take is that this was a very interesting discovery, but that they probably felt pressure to figure out a way to describe it as useful in the modern world. But we’ve known about the useful parts of this discovery for forever. Our clocks are all base 60. And our computers are binary, not base 10, just to start with.

We overvalue trying to make every advance in knowledge immediately useful. Knowledge can be good for its own sake.

“Having many more right triangles for a unit length” would have an incredible benefit in constructing enormous triangly things.

Instead becoming more acute about triangly things… we were more obtuse and went base ten

Well yeah, who’s got 60 fingers? I mean sure, there’s Fingers Georg, but that guy’s weird.

People used to count 12 knuckles times 5 fingers for a total base 60.

Using only 5+5 fingers is the dumbed down version.

Wasn’t it the Sumerians that did use base 60 and just went to counting knuckles and joints to get to the base 60 system … never fully understood it when I read about it either

Here is a demonstration

https://mathsciencehistory.com/2021/11/09/count-to-60-with-your-phalanges/

Sumerians and Babylonians used the same cuneiform writing system with a base of 6×10, but it seems like they also used to count to 60 as 12×5… and what we’re left with, is the simplified 5+5=10.

Also, we shall remember that:

𒀭 𒐏𒋰𒁀 𒎏𒀀𒉌 𒂄𒄀 𒍑𒆗𒂵 𒈗 𒋀𒀊𒆠𒈠 𒈗𒆠𒂗 𒄀𒆠𒌵𒆤 𒂍𒀀𒉌 𒈬𒈾𒆕

Now I’m wondering why the Babylonians didn’t have giant triangle shaped orbital habitats.

Base 60 is based.

Base 12 is a good compromise between math and meat imo

One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, to market, stayed home.

Some days I wonder what would be different if we’d evolved with six fingers on each hand.

We’ve evolved with 14 knuckles on each hand… and a brain that struggles to keep 7 elements at once in operating memory. You can also count up to 1023 with just 10 fingers (in binary). It’s not a lack of fingers problem.

I’m not sure what problem you’re referring to. I mean if we naturally leant towards base 12, I wonder what would be different, if anything?

The problem is our brains have a limited operating memory. People can (unless disabled) easily track 1 o 2 items at once, even 3, 4, 5… and start losing track somewhere around 6 or 7; 8 is considered exceptional.

That’s why kids don’t generally use their fingers to count 2+2, but start using them for “harder” operations like 4+4.

Base 10 is already past our brain’s limits… but we’re kind of fine with it because we can use our fingers (think of it as evolving at a time before formal education when most people were illiterate).

Base 60 is also past our brain’s limits, but it’s easily divisible into easy to track 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 pieces (aka $lcm(1…6)$), which makes it highly useful. The Babylonians still used to write it down as base 6×10, and it was common to count on knuckles and fingers as 12×5.

The uneducated populace picked up the easiest part of the two: 5+5.

if we naturally leant towards base 12

If we had 12 fingers, we could’ve as easily ended up using base 12, only thing different would be 1/3 would equal exactly 0.4, while 1/5 would equal 0.24972497… oh well, we’d manage.

If our brains could track 12 items at once however, then we could benefit from base $lcm(1…12)$ or 27720. That… is hard to imagine, because we can’t track 11 items at once; otherwise 27720 would jump out as “obviously” divisible by 11, 9, or 7.

They can math.

That’s very interesting. Thank you for giving us your insight on this.

deleted by creator

Maybe I’m an idiot but how would a base 60 system with “Cleaner fractions means fewer approximations and more accurate maths, and the researchers suggest we can learn from it today.” make any difference when computers are powerful enough to generate solutions to answer with more accuracy than is ever needed in real world applications?

None, in modern context we can work in any base we desire, all that basic stuff got generalized ages ago. No one is going to change computing systems to use babylonian-style. And the trigonometry stuff is the same thing we knew, but discovered earlier than the greeks.

It’s a important discovery for sure, especially for our understanding of ancient Mesopotamian cultures, but everything else is the authors and the article going bananas with conclusions.

That’s kind of what I figured. I wish journalism didn’t need to be so incredibly sensationalist. I understand that it’s because the majority of the populace has the attention span of a gnat but it doesn’t make me feel any less annoyed by it.

deleted by creator

Rule 4 of the community forbids changing the headline. So you’d really need to convince the mods.

Computers still run different algorithms internally, some of which are more prone to having undetected errors than others:

Computers use base 2, binary. Whether humans use base 10 or base 60 is irrelevant.

The algorithms coded into computers are not in base 2, though. Only operating functions of the computer itself are in base 2.

You don’t code in binary

Every thing you code is binary. You may write ‘15’, but the code your computer runs will use ‘00001111’. The base-10 source code is only like that for human readability. All mathematical operations are done in binary, and all numbers are stored in binary. The only time they are not is the exact moment they are converted to text to display to the user.

What do you mean algorithms are not in base 2? What else are they in?

Just because you have human readable code which uses base 10 doesn’t mean it isn’t all translated to binary down the line. If that’s what you’re referring to, of course. Under the hood it’s all binary, and always has been.

Because calculations happen in the form the calculation is written. The math is done in whatever base the algorithm is told to process in.

Okay, walk me through how you think the code an algorithm is written in gets processed by the computer step by step, please. How do you think a computer operates and is programmed?

Let’s say you have code to tell the computer to calculate 3 + 5, in, say, C, because that’s close to assembly. What happens on the technical level?

In sorry but you seem to be mistaking the fundamental distinction between what we are talking about.

So, I’m a writer, not a researcher, but I’ve found the more tools I have stuffed into my brain, the more likely it is that two different things clank against each other and create something interesting.

I don’t think this is something unique to writing fiction–from my understanding of history, there’s quite a few moments in science where two somewhat unrelated things bash against each other and spark a new idea.

Sure, computers can do things we already know how to do, but actual inventors/scientists/people making stuff still need to think up things first before you can computerize it.

It’s possible that this WON’T do anything new in the realm of math, but it might create a string a researcher in a different domain–history, linguistics, whatever–can pull on to unravel something else. A diverse tool set leads to multiple ways to solve a given problem, and sometimes edge cases come up where one solution actually is better in some niche application because of something unique to the way it is shaped.

You’re not wrong that people can take inspiration from many different fields, but wild speculation about what could happen can be done for any new development, which makes it pointless and tiring when overused.

To generate most* solutions.

But I see your point.

Almost everything we think of as Greek innovations was actually the Greeks absorbing knowledge from the civilizations to their east. Greece is just when our records traditionally went back to.

Not to mention that a lot of greek texts that survived only did so thanks to the Sassanids (Persians), since the newly christian Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine) began purging all that stuff because “god is all the knowledge you need”.

Later on, those texts found their way back into Europe through the then Arab conquered Spain

A quick Google search shows that this is entirely incorrect (both that they were only preserved in arabic and that they made it back to Europe through al-andalus) and it’s apparently a popular myth.

From multiple articles (there’s a plethora of sources): Classical Greek texts were preserved in the byzantine empire and most classical Greek texts that are known today, are translations from texts that were preserved in Greek (mostly within the byzantine empire). There are a few texts that only survived for a time as Arabic translations, but according to what I read, those are only few compared to what was preserved in Greek.

IIRC the real situation was that classical texts were traditionally kept away from most public eyes because they were written by pagans, but trusted scholars and religious officials would usually be able to gain access to them if they needed.

Huh, I’ll have to look further into that, then

Much appreciated that you take it this way. This is a breath of fresh air compared to late stage reddit.

Yeah fuck that upworthy spam. Here’s the original article from The Guardian.

Not significantly better:

“which scientists claim are more accurate than any available today.”

No they obviously do not. Yeah the fractions are easier in base 60, but they are not more accurate than just using rational numbers or radicals in any other base.I’m partial to base 36

-

“10” is a square that’s also the product of two squares, 4 and 9

-

highly divisible, being able to simply express halves, thirds, quarters, sixths, and ninths, also twelfths and eighteenths but those are less common portions in daily use

-

you can represent it as [0 - Z], as in “…8, 9, A, B, C…”, it’s literally achieved by just adding the alphabet to the numeral system.

-

It is significantly better, it’s not spam reposting crap.

Thank you. I wasn’t going to click on that trash.

deleted by creator

I love history and discoveries like this fascinate me, but do they serve any functional purpose? Does knowing that Babylonians understood angles change anything in my daily or long term life?

Not trying to be critical, just a question I often pose myself but have yet to think of a reassuring answer for.

It might give you new respect for the Babylonians, and act as a corrective to the modern tendency to assume superiority. It might enhance your sense of how similar we all are and how connected, and your kinship with people who lived millennia before you. If little discoveries like this make us just a little more sensitive to the transience of even the most sophisticated societies, the kinship of all people and the sheer length of human history compared to the shortness of our individual lives, it might make us just a little more considerate and respectful in how we treat our world and our peers. The value of such discoveries is their cumulative influence on our understanding of ourselves and how we fit into the world. It makes us wiser.

Beautifully put

If you’d read the article you might have an answer.

Learning new stuff could be good for your brain. Sometimes you just gotta learn for the sake of learning!

Well we knew that trig and angles and algebra existed long before the Greeks. Pythagoras took his theorems from Persia.

In terms of perfume together human history finds like this are pretty important though because it helps us fill in gaps in our knowledge

In terms of perfume?

Piecing lol autocorrect got me

It could potentially get you laid or land you a job. So, yes.

Article originally appeared 07/22/21. Any follow up?

Older even - 2017: https://www.sciencealert.com/scientists-just-solved-a-maths-problem-on-this-3-700-year-old-clay-tablet

The news articles seem a bit off though.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plimpton_322?wprov=sfla1

Move I’ve Pythagoras, it’s Nebuchadnezzar’s show now!

Drink more Ovaltine?

A crummy commercial? Son of a bitch!

This is cool and all, but it’s a 6 year old story.

I think you meant 3706 years old.

It was already known that the Sumerians were calculating ratios of triangles and applying knowledge of degrees to circle calculations thousands of years before Hipparchus’ work. Whether or not this small stone tablet indicates that the Babylonians had a rigorous system in the same manner the Greeks developed, remains to be seen.

Actually, history didn’t change it’s still the same as it always was. It can’t change anymore since it happened in the past.

actually history is just our collective understanding of the past, so if it changes, history changes

The events that actually happened in the past didn’t change. But history is not what happened. History is what we think we know happened.

If there is new information about events we didn’t know about before, history changes.

I think it’s fair to say that our understanding of history, something which can change because it’s always in the context of the present, has changed.

The past doesn’t change. History can change though.

Great input thank you!

I thought things felt a little different today